This Data for Action blog post is co-authored by project team members from the 2021 Inequity by Design report: Brock Grubb; Shannon Waits; Brian Chu; Shelby Cooley, PhD; Mercy Daramola; Christian Granlund; Kanza Hamidani; Jose Hernandez, PhD; Danika Martinez; Monali Patel; Natasha Rosenblatt; Annia Yoshizumi.

Stroll through many neighborhoods in King County and you’re walking through a history of racist gatekeeping. Redlining was a common practice and a gatekeeper of opportunity in housing policy that harmed Black, Indigenous and other people of color (BIPOC) in communities across the country. Using historian Ibram X. Kendi’s definitional framework, we understand it today as a racist policy because it perpetuated and sustained inequity between racial groups.

Just as the long history of systemic racism in housing has created economic and environmental impacts that reverberate today, the public education system has a long history of racist policies that have created barriers to opportunity. In the context of Washington State postsecondary pathways, a particular practice of racist gatekeeping persists in community and technical college placement policies.

English and math placement policies at Washington’s community and technical colleges act as gatekeepers to college-level courses for recent high school graduates. The policies cause disproportionate harm to BIPOC students and should be changed to improve racial equity in the system.

We were part of a team that took a hard look at current placement policies within community and technical colleges (CTCs) in the Road Map Project region. Our research, summarized in last year’s Inequity By Design report, included conversations with the region’s students coupled with analysis of student high school and college coursetaking.

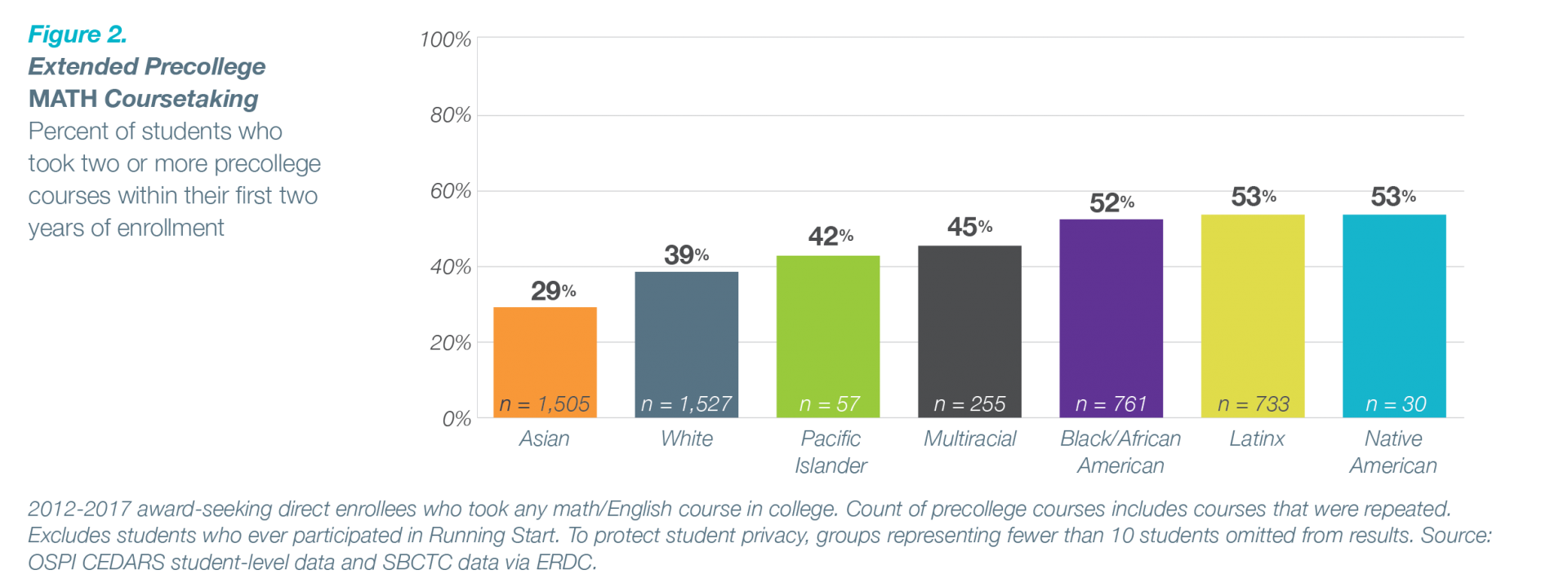

Our research found that CTC placement policies are racist because they systematically funnel BIPOC students into costly remedial (so called “precollege”) courses at far higher rates than their white peers. More than half of Road Map Project region direct enrollees who identify as Black, Indigenous, or Latinx took two or more precollege math courses compared to 29 percent of Asian students and 39 percent of white students.¹

Disproportionality and “underplacement”

The State Board for Community and Technical Colleges (SBCTC) has been looking at racial disproportionality in precollege placement for over a decade through the Transition Math Project, Rethinking Precollege Math and other projects. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) is very aware of issues of racial inequity in high school course access — they oversee a law requiring school districts to review racial disproportionately in course access on an annual basis. And Washington Student Achievement Council’s (WSAC), the state’s primary higher education coordinating body, has a strategic plan which clearly states that efforts to improve college enrollment “should be particularly focused on supporting students of color, especially Black, Indigenous and Latino students, who have been historically and institutionally marginalized from accessing higher education.”

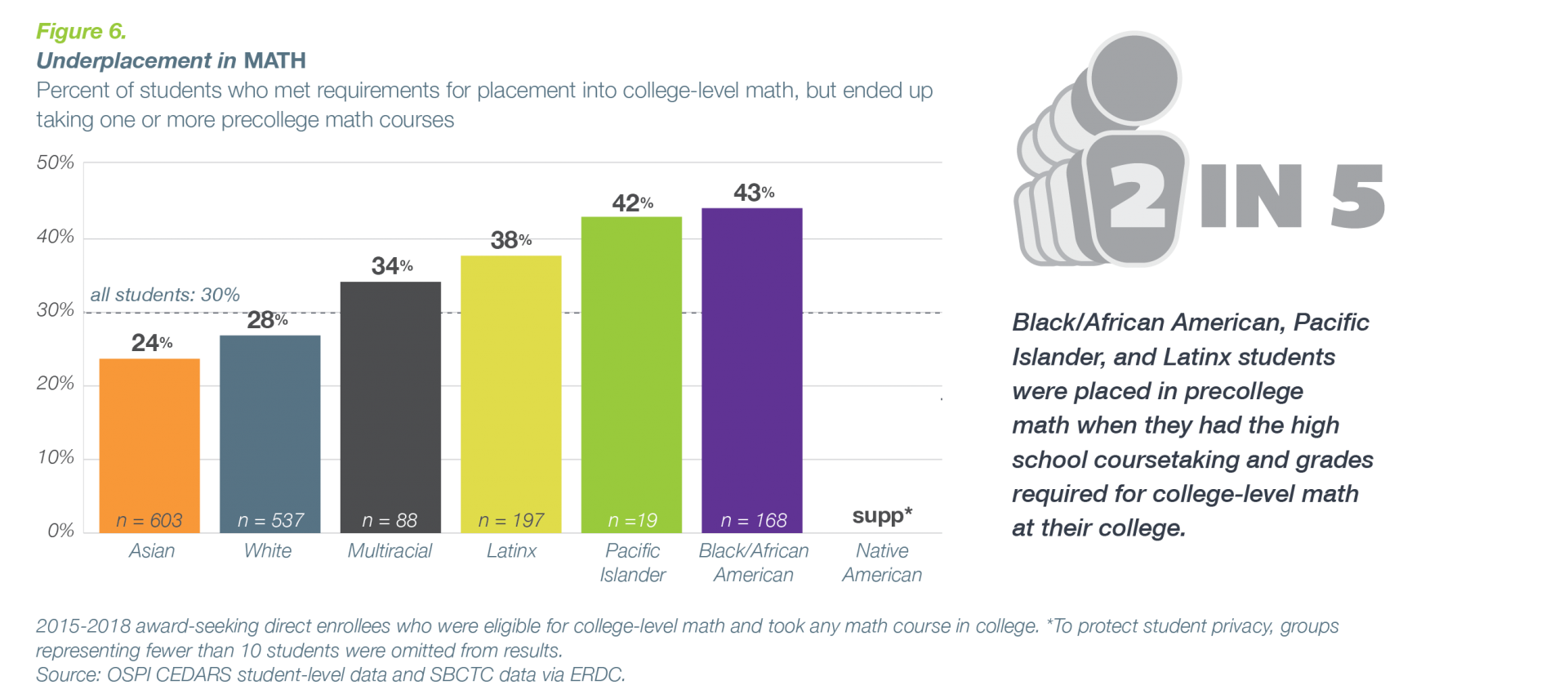

Despite these efforts, the latest statewide data makes clear that there is room for improvement: among 2019 high school graduates who enrolled directly at CTCs, college placement policies diverted 29 percent of students into one or more precollege course. These policies harmed BIPOC students at higher rates: 37 percent of Latinx students, 38 percent of Black students, and 44 percent of Indigenous students were diverted into one or more precollege course.

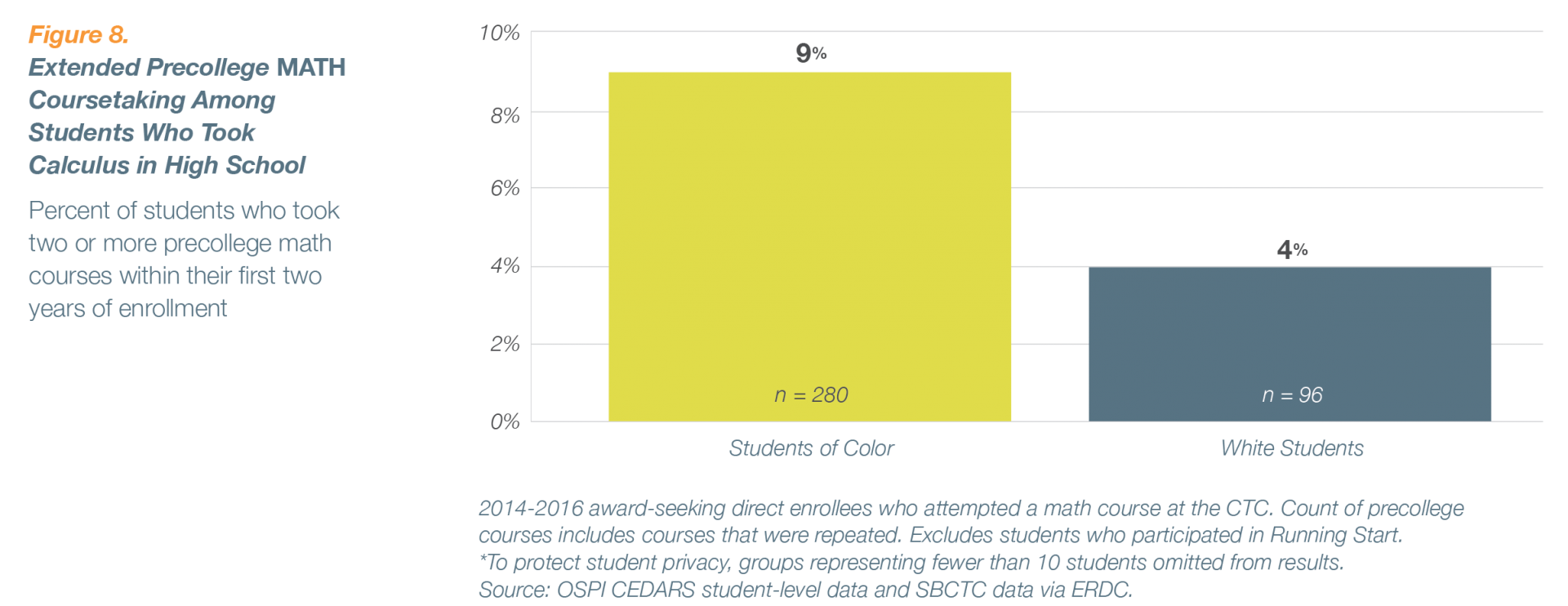

Our research suggests that many of these students — including a disproportionate share of BIPOC students — were underplaced, meaning they had the high school course grades needed to qualify for college-level courses but were diverted to precollege courses instead. These patterns held even amongst students with high GPAs and those who attempted rigorous courses like calculus in high school.

Moving towards antiracist placement policies

How can state leaders shift toward antiracist placement policies? They could start by reviewing the evidence coming from implementation of AB 705 in California. This equity-focused policy requires all community and technical colleges in the state to use high school transcripts as the default college placement approach and to take other steps to increase access to college-level courses in the first year.

According to evidence from multiple studies and a recent webinar about implementation of AB 705, these changes led to a statewide increase in access to transfer level math from 21 to 78 percent and the share of students who completed transfer level math in one year doubled from 26 to 50 percent. While implementation of the new policy has not been perfect, every college in the state experienced gains in completion of transfer level math courses. And the benefits didn’t just accrue to white students — completion of transfer level math in one year more than tripled for Black and Latinx students.

Our own work led us to make the recommendation that CTCs in the state make placement into college-level courses the default for all recent high school graduates. The good news is that all CTCs have the ability to make this change right now without the need for any new state policy action. Even more encouraging, the current Washington State policy that speaks to the function of a high school diploma suggests that signaling college readiness has been the role of a high school diploma all along: “the purpose of a high school diploma is to declare that a student is ready for success in postsecondary education, gainful employment, and citizenship, and is equipped with the skill to be a lifelong learner.”

CTC and state policy leaders in search of starting points — including those currently engaged in the Seattle Promise, the King County Promise and WSAC’s new Regional Challenge Grant program — can consult the full set of recommendations in the Inequity by Design report and the accompanying toolkit.

Moving to a diploma-driven college-level placement policy is even more important now given the racialized impact COVID-19 has had. In an attempt to mitigate the additional stressors put on students during the pandemic, the WA State Board of Washington instituted the Graduation Requirement Emergency Waivers program to enable students to waive selected requirements to allow them to graduate on time. As outlined in this recent brief, waivers were a helpful option, but resulted in many students waiving courses that could be used towards college placement. We need to ensure that students who received these waivers — predominantly students of color — don’t end up paying for these courses when they get to college.

Our “waterfall” moment

Change often takes time, but it can also happen all at once. Feminist author and activist Rebecca Solnit uses the metaphor of a waterfall to describe how once unthinkable policy ideas become inevitable. “The best ideas that change the world,” writes Solnit, “emerge from the shadows and the margins; they are at first ignored, then regarded with alarm or disdain by many outside those zones, and they work their way inward. When they are a consensus idea that’s…the waterfall, and politicians are smoothing things over and people have accepted the idea that they at first resisted, whether it’s the abolition of slavery or the right to marriage equality.”

Given the dramatic impacts of COVID-19, there is perhaps no better time to make placement into college-level courses the default for all recent high school graduates. If college leaders and state policy leaders act now, they can create a waterfall moment and end the racist placement policies that serve as gatekeepers between BIPOC students and their dreams.

¹As we note in the Inequity By Design report, current data collection standards limited our ability to conduct analysis using more nuanced racial/ethnic categories. It is important to note that these categories often minimize and erase the dramatically different realities that students experience across ethnicities within these broad race groupings. For example, throughout this report, there are findings where the results for Asian students are similar to white students. These aggregated results mask disparities that exist, and hide barriers that confront different ethnicities of Asian students. We encourage districts and colleges to further disaggregate these results in order to more deeply understand the experiences of students within their specific campus communities.

Posted in: College and Career Readiness , College and Career Success , Data and Research , Data for Action